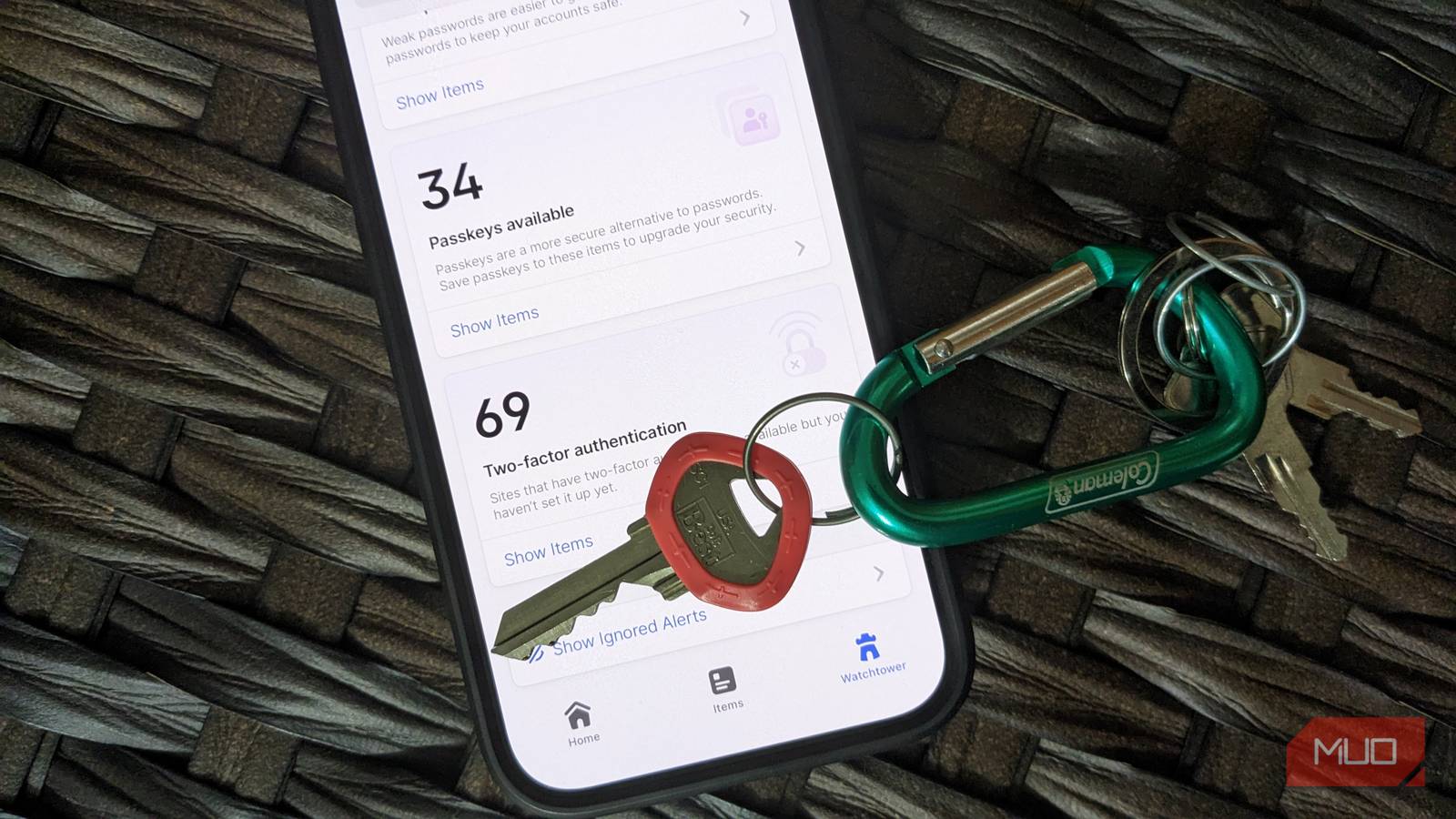

Over the past several weeks, I’ve taken the time to upgrade my online account security. This started with changing the app I keep two-factor authentication codes in; while doing this, I also decided to add passkeys to as many accounts as possible.

I like the idea of passkeys, and I’m glad to have the option. But as I worked through dozens of accounts, I wondered why something designed to simplify the complexities of passwords is implemented in such an inconsistent manner.

The quest to upgrade all my account security

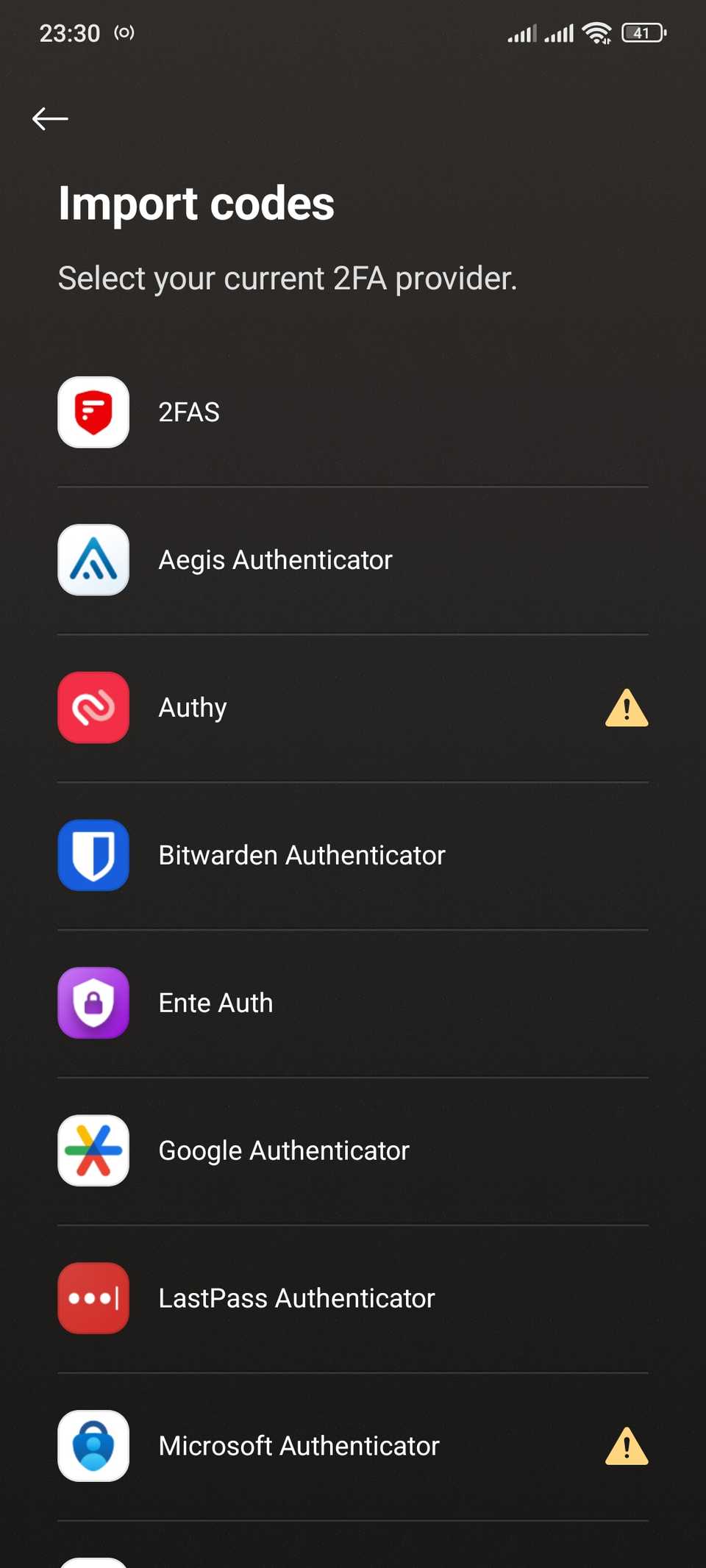

Back in September, I wrote about how I was switching my authenticator app from Authy to 1Password. Because Authy doesn’t allow you to export your 2FA secrets, this process involved manually visiting each account to disable and re-enable 2FA.

While I was in the settings for each account, I made sure that all my other security info was up-to-date. This included making sure my email address and phone number were verified, I had a backup recovery email set, and that I’d created a passkey.

As you’ve surely noticed, every aspect of account security is variable across online profiles. Some allow you to add many backup email addresses, while others only let you have one. Some use your phone number as a backup recovery method; others use this only for account communication.

Because passkeys are a much newer tool, I expected them to work more consistently across services. But as I added them wherever I could, I found this isn’t the case.

Passkeys don’t serve a single purpose

The stated point of passkeys is that they’re a more phishing-resistant form of authentication. You don’t have to remember one for every website, and you can’t accidentally hand a passkey over to a fake page. Thus, you’d expect that passkeys would replace passwords on many sites.

However, this isn’t what has happened in many cases. Instead, passkeys can serve as a password replacement, an additional option, or even a 2FA method.

Let’s look at some examples. When you add a passkey to your PlayStation/Sony account, it replaces your password and 2FA. You have to turn off passkeys to add a password again.

This is sensible, since using a passkey combines the work of a password and 2FA into one step. Sony implies that you don’t need those older options when you’re using their modern equivalent, which makes it strange that your security question (a far weaker method of authentication) is still active when using a passkey.

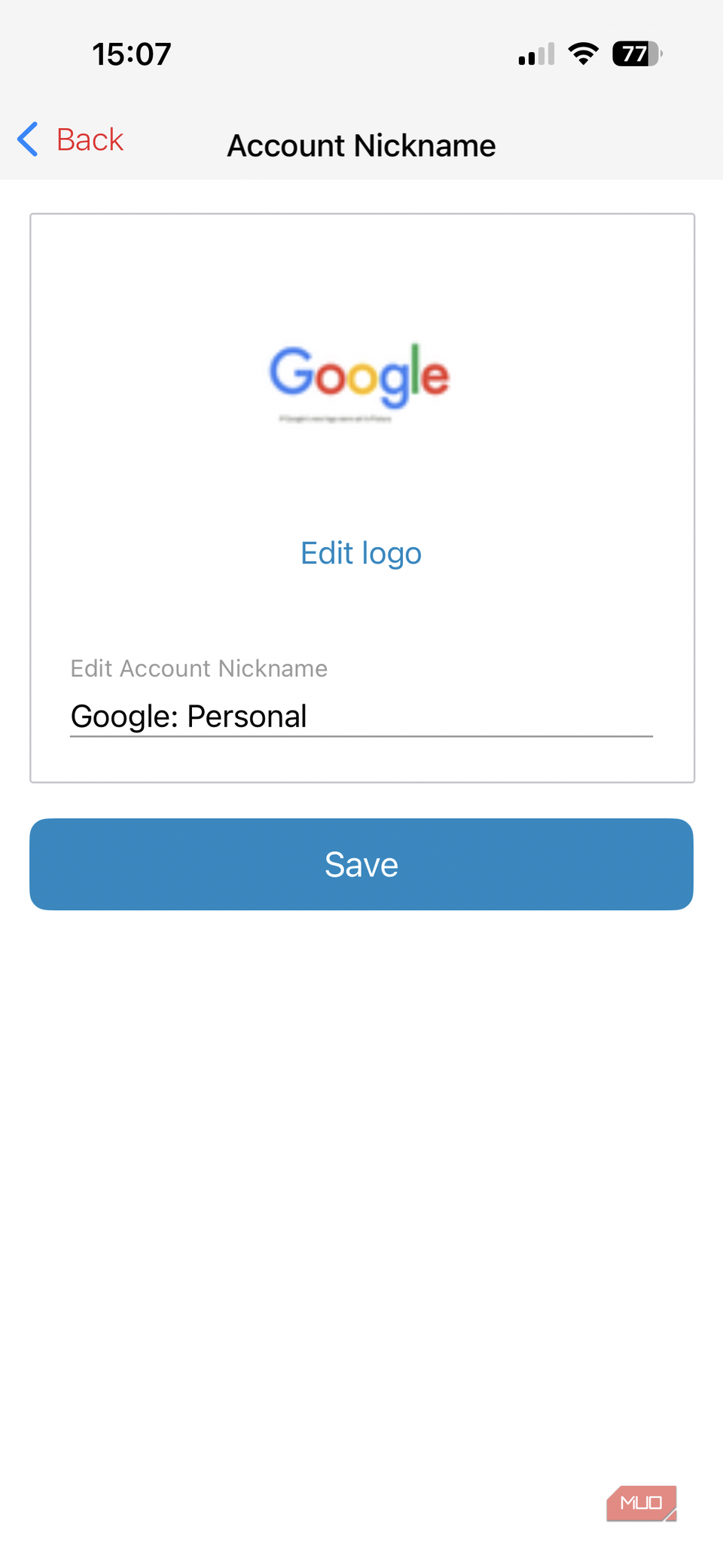

But that’s not the case for all accounts (in fact, few do this). With your Google account, you can enable Skip password when possible, but you still have the option to log in with your password instead of your passkey.

Meanwhile, the ID.me identity verification service supports passkeys, but only as a second factor. You still have to enter your password to start authenticating, but then you can use a passkey in place of a 2FA app code.

While I was logging into accounts to get screenshots, Battle.net didn’t ask me for my passkey at all. I had to enter my password and use the mobile app for 2FA. Why let me add a passkey if I can’t take advantage of its convenience?

Passkeys plus passwords are no better than passwords alone

Google’s approach is the most common implementation: using passkeys as the preferred method, but letting you use your password as a backup when needed. This is convenient as people get used to passkeys, since early on, you’re more likely to misunderstand how they work and accidentally lock yourself out.

But the downside is that with both passkeys and passwords enabled, your account is only as secure as your password is. It’s a security cliché that your account will only be as strong as its weakest link.

As passkeys become commonplace, I expect we’ll see more accounts disable support for passwords. Until then, baseline account security won’t truly be upgraded.

2FA is inconsistent, too

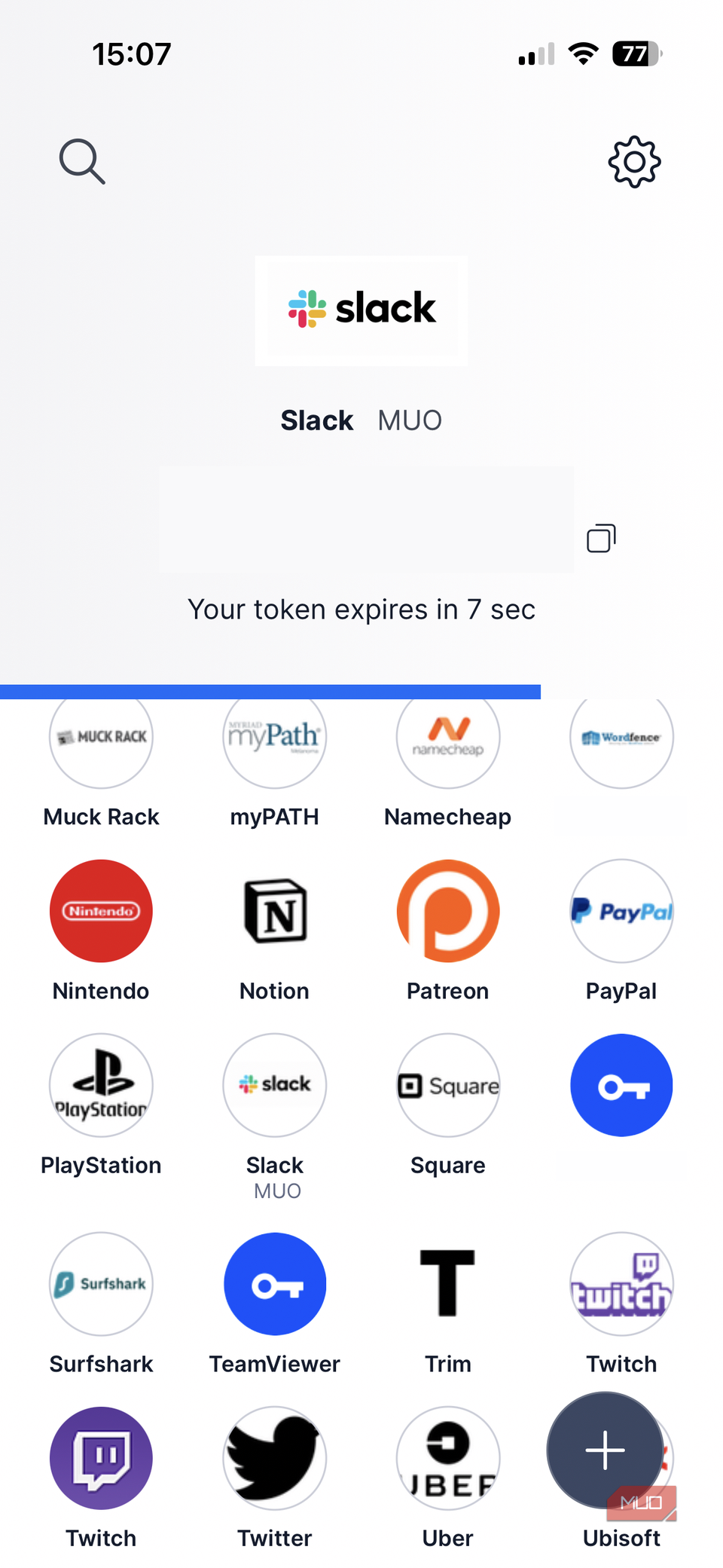

Passkeys aren’t the only element of this security journey where I found annoying inconsistencies. My preferred method of 2FA is TOTP (time-based one-time password) codes in an authenticator app. Most services let you use any 2FA app you like by scanning a QR code or entering a secret.

I found an exception to this: ID.me (making it a security oddball in two ways). It has its own authenticator app called ID.me Authenticator, and you can’t use any other option. Both 1Password and Proton gave me an error when I tried scanning the QR code, and I couldn’t manually enter the secret.

I added 2FA to my ID.me account in 2022 using Authy, so this must have changed in the last few years. Since I was trying to condense the number of apps I use, I’m not thrilled about having to add another app to my phone (that I can’t access on my computer) for a single website.

I noticed that Google prevents you from using SMS for 2FA when you have more secure methods (like an authenticator app) added to your account. Given that SMS and email are the weakest 2FA methods, pushing you away from them is wise.

But this isn’t consistent across accounts either—some services require you to have SMS 2FA enabled as a backup, others allow you to, and some don’t support it at all. While it helps us feel better about our account protection, it’s fair to say that 2FA is one of the worst technical hurdles we put up with.

Another oddity that always throws me off is when the website asks you to confirm your phone number or email address before sending you a code (Microsoft does this). Because almost every other site sends the code immediately, I gloss over the prompt and end up waiting a minute or two, wondering why I’m not getting the code.

Stronger security isn’t always straightforward

After a lot of tedious work, I’m happy with the state of my account security. Passkeys are (usually) implemented clearly, and almost every site supports 2FA authenticator apps. I cover this lack of consistency because if I noticed it as someone who works in tech, I’m sure people who are less tech-savvy will, too.

These bits of confusion add up, especially when making mistakes in this area can lead to you getting locked out of your accounts. If passkeys are going to take over passwords, they need to be implemented in a clear, consistent way so everyone can take advantage of them.