I get the impression that a lot more people are thinking about web browser privacy than they did a decade ago. I don’t have a survey at hand, but considering how widespread news and advice pieces are about the topic — and how often browser makers themselves tout privacy features — there must be some groundswell of awareness. It’s also difficult to ignore the consequences of weak privacy, since pretending that it doesn’t matter will result in obnoxious advertising at best, and a compromised device or identity at worst.

It’s actually taken for granted these days that a web browser will offer some sort of private browsing mode. If it’s not called that, it’s going to be called something like Incognito, as in the case of Google Chrome. But how secure are these modes, really? The details are going to depend on the exact browser, but the short version is that you shouldn’t depend on these modes as some sort of bulletproof shield.

What do private browsing modes actually do?

Local privacy over wider protection

Something all private modes share in common is that they’re isolated from other tabs, and won’t save your site/page history. If we’re honest, this is most often used to look at… certain images and videos on a shared device, but it might also be handy if you’re shopping for a birthday present or engagement ring. Additionally, it could be necessary if you want to research a particular political or religious view without someone judging you harshly, which is all the more likely if an infamous website shows up unexpectedly in that person’s auto-complete suggestions.

Tracking and preference cookies aren’t saved, and all third-party cookies are blocked by default — at least in Chrome, Safari, and Firefox.

That leads me into another common trait, which is that tracking and preference cookies aren’t saved, and all third-party cookies are blocked by default — at least in Chrome, Safari, and Firefox. This is useful not only for reducing the degree to which you’re tracked (more on that in a moment), but for preventing advertisers and other parties from completely misjudging your interests. Using the political example, you might be doing research on far-right politics for a news agency or civil rights group — in which case you wouldn’t want anyone getting the impression that you actually support them.

Once a private tab is closed, all of its data is scrubbed from your browser, at least on paper. That’s going to make things inconvenient the next time you revisit any websites, so you should probably avoid using private browsing all the time unless your needs are limited or severe.

So what’s the problem with private browsing, then?

Dealing with the realities of the internet

The ugly truth is that cookies aren’t the only way you can be tracked. Another is “fingerprinting,” used to identify a person by common factors, even if you technically remain anonymous. Whenever you visit a website, it still needs basic pieces of information to serve you, such as the browser you’re using, the device you’re using it on, and what your IP address is. Chrome on a Windows laptop renders things in a different way from Safari on an iMac, and of course, any site needs to know where it’s sending data.

Fingerprinting works because it’s rare for two people to share the exact same profile. There aren’t going to be many people visiting a specific website from a specific IP range using a specific web browser operating at a specific resolution. If you can narrow things down further, you can tell when that person is active on another website, regardless of whether cookies are active. Data brokers and the like are especially interested in this, since it lets advertisers target you with eerily precise demographic content. It might be one of the reasons I see so many ads for EUCs these days.

Fingerprinting is used to identify a person by common factors, even if you technically remain anonymous.

On a deeper level, a private browser isn’t going to stop your internet provider (ISP), network administrator, or other party with direct control over your web traffic from seeing the sites you access. They need to know this for practical purposes, at least. They may not care what you’re visiting, most of the time — but if they’re served with a warrant or a national security order, they may have no choice but to hand over that information.

ISPs may also voluntarily rat on you if you’re suspected of piracy, and of course, some governments have no qualms about spying on innocent people.

What can I do to make private browsing more private?

You’ve got options

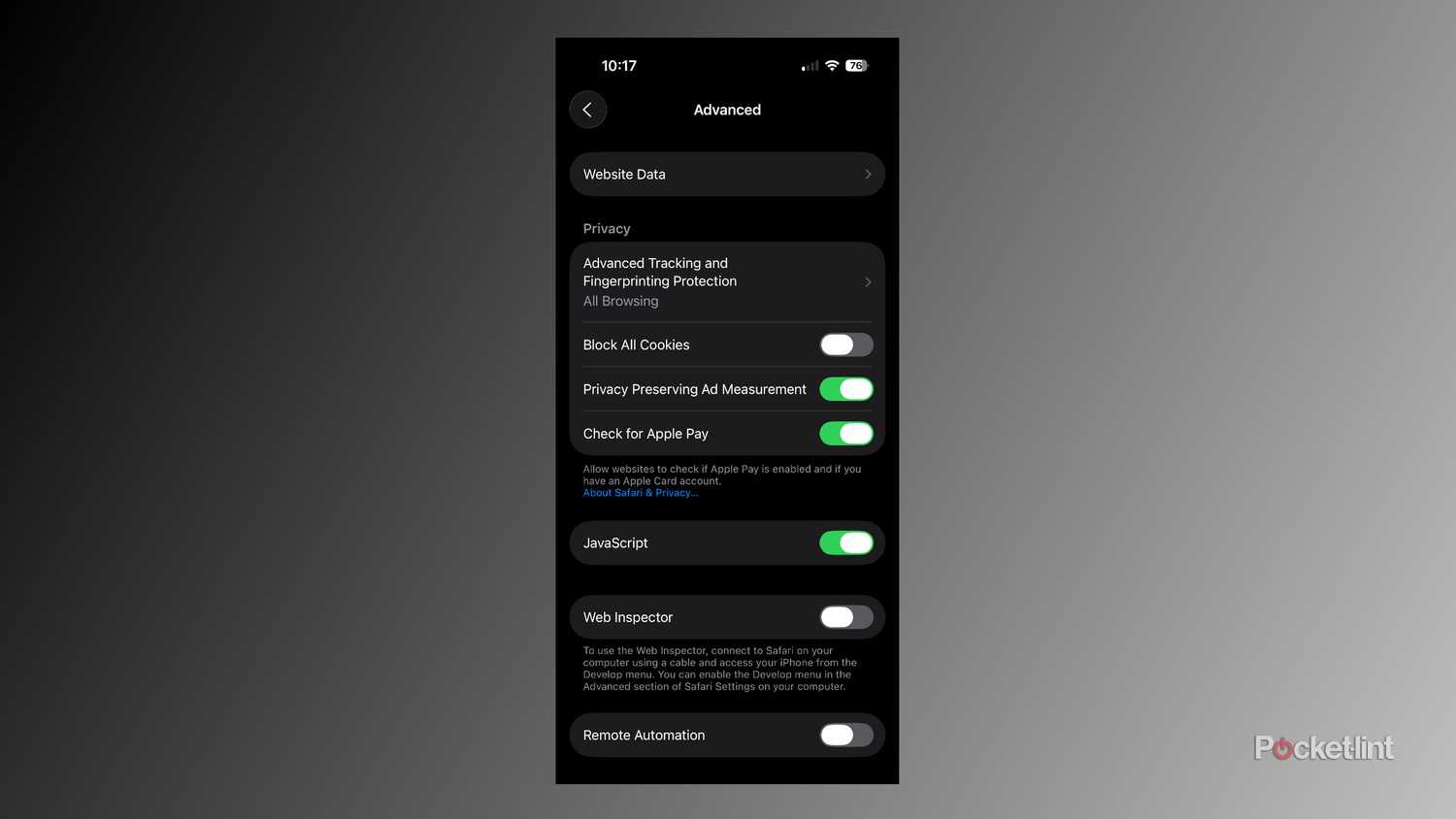

The good news here is that you’ve got a variety of tools at your disposal. The most basic is to turn on any anti-fingerprinting protections your browser might have. These are baked into Safari and Firefox, but with apps like Chrome, you may need to turn to third-party extensions instead. Be warned that anti-fingerprinting measures can potentially cause havoc — since they’re either blocking data or injecting artificial “noise,” even some innocent sites may not behave the way they’re supposed to. You’ll have to decide for yourself how much you care about this kind of tracking.

The most extreme option is Tor Browser, one of the tools of choice for dissidents monitored by authoritarian regimes.

The next step for some people will be turning to a VPN (virtual private network). By their nature, VPNs disguise your IP address for any site you visit. They also encrypt traffic while it’s en route, making it tough or impossible for outside parties to intercept, and may have additional security measures on top of that. If you’re worried about surveillance, a VPN is probably unavoidable, although not some sort of magic wand. You’re not going to escape the Great Firewall using a VPN tolerated by the Chinese government.

Some third-party browsers place stronger emphasis on privacy, such as Brave and DuckDuckGo. The most extreme option is Tor Browser, which routes your traffic through the free Tor network, and is one of the tools of choice for dissidents monitored by authoritarian regimes. It should probably be avoided by casual users, however — it slows down your web traffic, and many plug-ins simply won’t work. Indeed the Tor Project recommends against installing any plug-ins that might work, since they could bypass the Tor network or otherwise leak your data. The group is deadly serious about its mission.